64 Wimpole Street

London W1G 8YS

Thursday November 3

2016

It would seem perverse

if you had an appointment at the dentist, for actual treatment, to be visiting the Dental Museum barely an hour before but that was the situation for one of us

this week. It was partly the proximity as Wimpole Street for over a century has

been the ‘go-to’ address for private doctors, many of whom can still be found

here between the institutions and august

bodies – Number 1 is the HQ for the Royal Society of Medicine, the nurses were

round the corner – but today we were heading for the dentists. Many of the

houses are sturdy and handsome Georgian terraces but the BDA must have

been ‘filling’ (Ho-ho) where a gap

appeared as the building dates from 1967. (By the way the numbering is so

long-established the numbers go up one side and down the other – none of that

odds and evens business.)

As Jo said, dentists

are in the main disliked not for who they are but for what they do, which is

often to cause pain, so everyone at the BDA was totally charming and welcoming.

It is their professional body so there are numerous meeting and lecture rooms

and we were directed to the museum, which is just off the library/archive on

the ground floor. I suppose with the exception of the large chairs (and there

is one of those on display) and the spittoons much of what dentists use comes

small and the exhibits are well displayed and well captioned in a handful of

themed cabinets.

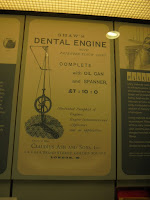

You are drawn into the

exhibition by a series of early/mid-20th century posters encouraging

parents to care for their children’s teeth – save those precious little pearls.

Baby teething is a fairly brutal process and truth to say teeth can cause

discomfort throughout life. Sadly Jo and I belong to what is known in the trade

as ‘the heavy metal generation’ namely post war children where a combination of

sugar coming off rationing, Vitamin C supplements coming in syrupy forms and

relative ignorance about tooth care means we have more fillings than teeth,

whereas the next generations benefited from the addition of fluoride and more

awareness of the damage of sugar in all its forms.

But back to the museum

which is arranged thematically.

Dentistry has a very

short history compared to medicine – the first text book appeared in 1728 in

French whilst in the UK it was mid-19th century before practitioners

started researching, writing and practising in a more coherent way: up until

then any ‘dentistry’ (more likely brutal extractions) was done by the barber or

the blacksmith, the latter having the tools. Sir John Tomes, who is honoured

here, not only helped improve the instruments and the research but also became

a lecturer and founded the British Dental Association in 1880. Up until then

practitioners needed no qualifications and anyone could call themselves a

dentist – it was as late as 1921 that the Dentists Act finally ensured those

extracting and filling your teeth had been appropriately trained.

Decay is easy to spot

and there are several examples of rotted and sometimes filled teeth that were

found in the remains recently excavated in Farringdon as part of the Elizabeth Line construction works.

Though some of these

sets of teeth are probably later, there being perhaps several different ages of

burial ground? One set is filled with a

little gold – unusual in what might have been a paupers’ burial site but who

knows how anyone landed up there?

The 20th

century saw advances in drilling and filling (there are foot and hand operated

drills for you to try, making early dentistry seem quite a ‘physical’ job) with

the invention of amalgam

Jo and I certainly remembered

those early heavy slow drills then replaced by higher speed ones – no sound

effects at the Museum but it did not need much imagination to remember the earlier ones, a small scale

woodwork drill only noisier, let alone the whine of the current ones.. Gold has

long been a favourite material for fillings and crowns as it is totally

tasteless and does not decay or crack, yet can be moulded accurately, so it

remains a preferred material.

Of course if drilling

and crowning does not work the next stage is extraction (multiple forceps on

display) followed by ‘false teeth’. Again the evolution here is interesting –

ranging from small carved bits of ivory (hippo or walrus being the most

favoured), which are then tied in place with fine silk threads – how insecure

this must have felt? The big revolution came when vulcanite was invented (by Mr Goodyear).

The 20th

century not only saw a range of new materials open to the medical and dental

professions but with the proliferation of professional expertise (the first

dental school was opened in 1889) there

were also dental dispensaries for the poor before the advent of the National Health

Service.

Alongside these

technical innovations the profession also used anaesthesia – I will not

elaborate as we have already visited the Centre for Anaesthesia and it makes for strangely bland and

uninteresting displays.

Not so the section on

Prevention – from the jolly posters advocating better care of your children’s

teeth to early toothbrushes made of bones (the handles) and pig’s hair… There

is everything here from novelty toothbrush cases to early forms of tooth

powder. William Addis produced the first toothbrush

(there’s a nice little

film here if you can get your computer to load it). Preventive dentistry became

serious after the First World War when the Services realised that significant

numbers of recruits were turned away because of poor or rotten teeth.

This concludes the

main exhibition but we were encouraged to go downstairs where there was a

special exhibition on dentistry during the First World War when their skills

were needed not so much for the day to day fillings etc but for repairs

following serious facial injuries. This is where dentistry meets up with

maxilla-facial surgery, a later surgical speciality.

We thought the

displays were well presented – rather than cases full of similar instruments

they explain more fully, and in a very accessible way, including some films, the history and use of key items and

significant developments acknowledging the pioneers of their profession. In amongst the exhibits are frequent cartoons

(not easily reproduced) and other humorous touches – we liked the tooth shaped

(perfect of course) stools, and the ‘shop’ made an instant sale with its

clockwork chattering wind-up teeth.

Next step – book that

check-up…

Eurosharp is a diversified medical and salon store, created with the vision of Sam to provide you with unique medical and salon accessories. Founded in 2019, located in Manchester, Eurosharp brings you dental kits, dental articulators, barbar scissors and razers , orthopedic and ENT.

ReplyDelete