Thursday 25 May 2017

This was a doubly exciting outing for Linda and me: firstly, because we like a new museum, and secondly because we were to be accompanied by Nick Patrick of BBC Radio 4's Making History programme, together with his interviewer, Iszi Lawrence. The Museum is where the Clockmakers' Museum used to be before it moved to the Science Museum, so we did not get lost. It is part of the complex which includes the Library, and is not large. Indeed, the shop which contains books, biros, bears and everything else you might expect, is in the Library.

This was a doubly exciting outing for Linda and me: firstly, because we like a new museum, and secondly because we were to be accompanied by Nick Patrick of BBC Radio 4's Making History programme, together with his interviewer, Iszi Lawrence. The Museum is where the Clockmakers' Museum used to be before it moved to the Science Museum, so we did not get lost. It is part of the complex which includes the Library, and is not large. Indeed, the shop which contains books, biros, bears and everything else you might expect, is in the Library.

The Museum begins, appropriately, with the oath that the constables take, and the we had a run through of the history of policing in this small but venerable part of London.

The Museum begins, appropriately, with the oath that the constables take, and the we had a run through of the history of policing in this small but venerable part of London. From the reign of Charles II, each ward had to provide watchmen, known as Charleys, after the King. But because City money talked, even then, many of the watchmen were paid substitutes, decrepit and elderly. From 1737, there were marshals, armed with swords and truncheons. Different guilds paid for the service, and we saw a truncheon with the wheat sheaf of the Bakers' Company.

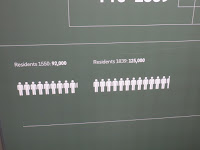

From the reign of Charles II, each ward had to provide watchmen, known as Charleys, after the King. But because City money talked, even then, many of the watchmen were paid substitutes, decrepit and elderly. From 1737, there were marshals, armed with swords and truncheons. Different guilds paid for the service, and we saw a truncheon with the wheat sheaf of the Bakers' Company. Throughout the exhibition there are what I believe are called infographics, about the population of residents and workers in the city.

Throughout the exhibition there are what I believe are called infographics, about the population of residents and workers in the city. Unlike any other part of London, the population of residents has gone steadily down, while the number of workers goes up. and this has been reflected in the number of police officers

Unlike any other part of London, the population of residents has gone steadily down, while the number of workers goes up. and this has been reflected in the number of police officers A very interesting exhibit was the wooden model made by police technicians for use in court in 1911, to demonstrate what happened in a robbery and murder. Nowadays, what with computers and such, this another lost skill.

A very interesting exhibit was the wooden model made by police technicians for use in court in 1911, to demonstrate what happened in a robbery and murder. Nowadays, what with computers and such, this another lost skill.The Museum has more to read than many museums. Comparatively few objects, though all of them significant, and plenty of photographs.

Material about anarchists, the Houndsditch murders and the Sidney Street Siege included a Daily Graphic front page, referring to 'foreigners' as well as the wanted poster as printed in English, Russian and Hebrew, reflecting the mixed population of the area. The widows of the three police officers who were killed, were awarded pensions of 30 shillings a week for life. This would be about £400.00 today, which is not unreasonable. They were also told that there were vacancies at the Police Orphanage in case they needed help with their children

Material about anarchists, the Houndsditch murders and the Sidney Street Siege included a Daily Graphic front page, referring to 'foreigners' as well as the wanted poster as printed in English, Russian and Hebrew, reflecting the mixed population of the area. The widows of the three police officers who were killed, were awarded pensions of 30 shillings a week for life. This would be about £400.00 today, which is not unreasonable. They were also told that there were vacancies at the Police Orphanage in case they needed help with their children Officers had access to medical care, and the City provided electric (later petrol) ambulances from 1907 until 1949 when the NHS took over. They were, in the main, a healthy lot, however, and had opportunities for sport. In 1920, the City of London Police became Olympic Gold Medallists for the tug-of-war, a record they still hold, since the event was removed from the Olympics from 1924 on.

Officers had access to medical care, and the City provided electric (later petrol) ambulances from 1907 until 1949 when the NHS took over. They were, in the main, a healthy lot, however, and had opportunities for sport. In 1920, the City of London Police became Olympic Gold Medallists for the tug-of-war, a record they still hold, since the event was removed from the Olympics from 1924 on.There was a substantial section about the two world wars, including photographs taken by police officers. Between October 1940 and June 1941, 271 HE bombs landed in the city. By the end of the war and the use of the Terror weapons, one third of the city had been destroyed. We saw police issue gas masks. Another effect of the war is that the City force began to recruit women to fill the gap.

We saw a photographic display about police horses and police dogs, as well as a mock up of a police switch-board (aah, the days before mobile phones,,,,)

We saw a photographic display about police horses and police dogs, as well as a mock up of a police switch-board (aah, the days before mobile phones,,,,)  And we liked a police box, since nowadays, you mostly see them on Doctor Who rather than in real life.

And we liked a police box, since nowadays, you mostly see them on Doctor Who rather than in real life.The city is of course a major potential target for terrorists, and there was a section about this. The well known photograph of Mrs Pankhurst being arrested in Westminster was perhaps stretching the remit a bit - Sidney Street might have been a better lead-in - but the display was thoughtful. And of course given the events of Monday in Manchester, particularly thought provoking. Sadly, the interactives about being able to spot suspicious things and people was not working. Information about the 1972 Ring of Steel and the 1973 bomb at the Old Bailey reminded us that the police need to be vigilant

Cases full of uniforms through the ages did not excite us, though they are an important part of the story. Unsurprisingly, the Museum has a dressing up area where you can try on various helmets and caps. There was also a case of items used in violent crimes through the ages, but we were not allowed to test them out!

Cases full of uniforms through the ages did not excite us, though they are an important part of the story. Unsurprisingly, the Museum has a dressing up area where you can try on various helmets and caps. There was also a case of items used in violent crimes through the ages, but we were not allowed to test them out!And the last infographic about how many people are being policed, showed that in 1994 there were 6,000 residents and 270,000 workers

All in all, we enjoyed the hour that we spent here. Unlike some museums in the city (Bank of England, for instance) it is open on Saturdays and well worth a visit.